My progress, though, has come to something of a blockade.

I've been doing a weight lifting routine that I'm happy with. It includes the use of barbells for squats, but I need weight that's heavier than what I can safely lift over my head to put back on the floor. I need (gulp) a squat rack.

In my gym, there is a clear segregation going on with the weights. On one side of the gym, there's cardio equipment and a set of lightweight dumbbells, some medicine balls, some lightweight machines, and some kettle bells. On the other side of the gym (separated by a wall and a hallway), there are heavier weights, freestanding barbells, and more substantial machinery.

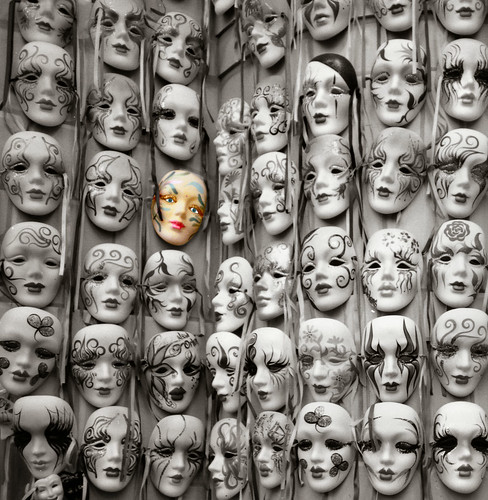

It's probably no surprise to you that there's something of a gender divide in their use. The lighter side has a good number of men, but it's often dominated by women. The heavier side is almost always men and one incredibly badass looking woman (there's more than one woman, but there's only ever one at a time. It's some kind of physics rule, I think).

I want to be the incredibly badass looking woman, but I'm not. I have, however, forced myself to make the trek from the light side to the heavy side because that's where the weights I need live. It makes me feel out of place. I am always intimidated and afraid that I'm standing in someone's way, doing my measly twenty-pound dumbbell curl while the guy next to me bench presses a small horse worth of metal.

I don't think anyone's actually judging me. I've never gotten rude looks or comments. Everyone has always been nice. The problem here is in my own head, and I know that, but I don't know how to get it out.

It's time for me to get in the squat rack, but all I can think about is what happens if I put on too much weight and drop it or if I do it wrong and look ridiculous. I'm not even really afraid of hurting myself (unless you count an injured ego).

You know that feeling you get when you accidentally walk into the wrong restroom? That's how I feel when I'm lifting weights: a vague sense of not belonging. Walking up the squat rack feels a little like walking up to a urinal; it makes it clear that I'm not just accidentally in the "wrong" space, but actively declaring my right to be there for its intended purpose. I know that's exactly why I need to actually do it, but it still makes my heart race and my palms sweat, and that makes it harder to hold the bar.

You know that feeling you get when you accidentally walk into the wrong restroom? That's how I feel when I'm lifting weights: a vague sense of not belonging. Walking up the squat rack feels a little like walking up to a urinal; it makes it clear that I'm not just accidentally in the "wrong" space, but actively declaring my right to be there for its intended purpose. I know that's exactly why I need to actually do it, but it still makes my heart race and my palms sweat, and that makes it harder to hold the bar.

Photo: Jason and Tina Coleman