Sullivan reflects on the need to consider the history of composition studies' egalitarian aims and then question how those aims have been enacted in actual teaching practices:

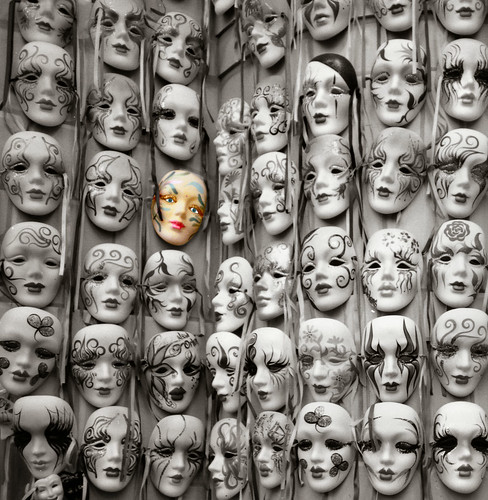

Many composition scholars and teachers served as advocates for all students' rights to literacy regardless of a student's age, race, gender, socioeconomic background, or national origin. It is composition's humane disregard for difference under an egalitarian ethic, however, that now renders it pervious to feminist inquiry and critique. For the assumption of equality tends to mask difference.

She goes on to give an example of a time she herself fell into this trap while evaluating a student's work. A female graduate student with a male professor was not doing well in class. When Sullivan looked at her work, she focused on "the disjuncture between her writing performance and her teacher's expectations." The student's style was more exploratory (a style we often consider "feminine" because of its sometimes passive exploration) while her teacher was insisting on a more critical mode of inquiry (a style we might call "masculine" for its aggressive nature).

Sullivan admits that she "'saw' deficiency where she might only have seen difference."

"Had I interpreted her experience through the lens of gender," Sullivan notes, "I might not have concluded that I had observed a substandard writing performance born of inexperience, but only a nonstandard performance in a course where male conventions of discourse were allowed to define the standard."

Substandard v. Nonstandard

There is a standard. There is a normal. There is an expected.

In some ways, there has to be. We are social creatures, and we learn a lot in the aggregate. We combine differences until they are blurred so that we can rest on a set of comfortable assumptions about how things are "supposed" to be. It is a meaning-making shortcut.

So while it may be impossible to do away with the concept of a standard, it is not impossible to question how we use it. Instead of seeing every deviation from the norm as "less than" (substandard), we need to consciously force an inquiry that determines whether that deviation may simply be different (nonstandard).

This has real, important, life-changing impacts.

When I had that debate with the aldermen about the proposed sagging pants ban in St. Louis, I was on the phone with my ward's representative. One of my arguments was that this law would be enforced along racial lines. I pointed to the fact that St. Louis arrests black people at 18 times the rate of white people for marijuana offenses despite similar rates of usage. He quickly countered that he knows white people who smoke marijuana, but they do it in the privacy of their own homes where no one can see them. "They're not out on their front porch doing it!" he cried.

Obviously, he's making some pretty sweeping generalizations about who uses marijuana how, but let's go ahead and take him at his word for the sake of argument. White people smoke weed behind closed doors; black people do it on their front porches where they can be seen. The implication is that the white choice is the standard ("Sure, everyone does it, but these people do it the right way.") To then say that a deviation from that choice is substandard (and thus deserving of an arrest) ignores the inequality present in what gets read as a "criminal" act.

In fact, that's what was at the heart of the sagging pants ban to begin with. Sure, sagging your pants is a nonstandard way to dress, but to criminalize it assumes that it is a substandard way to dress. Meanwhile, fashion trends that are also nonstandard but aren't racialized are not treated the same way.

We might snicker or be amused by a nonstandard display of a man walking around in lederhosen, but it's highly unlikely that we actively criminalize the act and devalue the person as substandard.

These assumptions of substandard acts get used along lines of power all the time.

Consider this woman who was kicked out of a water park for wearing a bikini. She was surrounded by women who were younger and thinner than her in the same attire, but her body was considered substandard instead of simply being nonstandard. Similarly, women are frequently harassed and harangued for breastfeeding their children (need proof? Go to the Twitter feed of @BoobsR4Babes). The amount of exposed breast during a nursing session is usually far less than that on display in every grocery store magazine aisle, but sexualized female bodies are standard, so nurturing bodies are seen as substandard.

Scrambling to Maintain Power

The benefit of making something substandard instead of nonstandard is that it gives the powerful a greater chance of maintaining their power. If breastfeeding is stigmatized and even outright banned, then it is much less likely that women will do it. If women don't do it, then it doesn't become normalized and there's less risk to those who maintain power by keeping women locked into a sexualized role.

If sagging pants are stigmatized and criminalized, then it is easier to criminalize and stigmatize the entire culture with which they are associated. Making sure that the hip hop culture is seen as substandard instead of nonstandard ensures that the valid political and socially-conscious messages coming out of that culture remain in an echo chamber.

That scramble for power is then maintained throughout the layers of American culture. When someone like Don Lemon comes forward to blame black social problems on the inability of black people to act in the "right" (read: white) way or we say that breastfeeding mothers should simply take their hungry babies into a bathroom, we ignore the systems of oppression at play in making us believe in those standards to begin with. We begin to accept the standards as inevitable and set rather than mutable and constantly negotiated.

We, in short, ensure that the people in power won't have to share any of it.

Question and Conquer

Let's go back to the quote I used at the beginning of this article: "the assumption of equality tends to mask difference."

We are told over and over again that everyone is equal. We are often told that we live in a post-feminist, post-racial world where women are graduating from college at higher rates than men and we have a black president so the social ills of the past are just that, in the past.

This is a nice narrative, and I understand why someone would want to just accept it and move on. The belief in an egalitarian meritocracy where everyone gets what they deserve based solely on his or her individual merit is an attractive one.

But we have to make sure that believing everyone has the right to equal treatment doesn't translate into believing everyone has access to equality. We have to make sure that we haven't put on blinders to any oppression that doesn't personally touch us. We have to make sure that we haven't just taken our own experiences as "standard" and decided to read anything else as "substandard," a sign that the people acting that way have made a poor choice and are thus responsible for their own victimization.

It's easy to stand on our own perches and decide that everyone else could stand there if they wanted to, that it was easy for us to get there so it should be easy for anyone else as well.

It can be easy to ignore how much fitting into the standard is really just a matter of luck (and privilege) and not the matter of personal choice we like to think it is. It can be easy to try to create "equality" by insisting that everyone else stand where we stand.

But the world is big, and there are lots of places to stand.

No comments:

Post a Comment